Kia ora – a largely off the cuff piece.

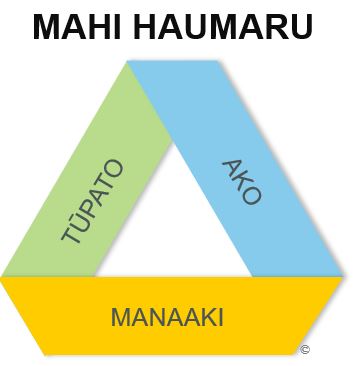

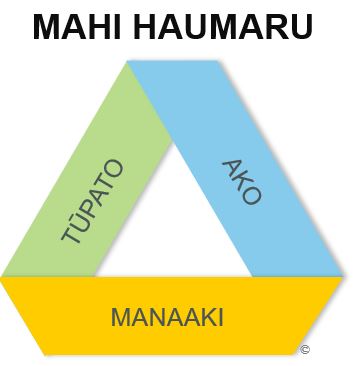

For the last few months I have been thinking about a possible model for understanding what good Māori health and safety could look like. I aimed for something that portrayed a simple three part structure that could resonate with Māori.

The Mahi Haumaru (Work Safe) Model has a long way to go, even as its architect, I’m unsure what it will finally look like, but at least it’s a peg in the ground.

In this post I discuss one of its elements – Tūpato.

Tūpato

Kia tūpato, tūpoto or matawhāiti is generally accepted as meaning to be careful or cautious. The cautious nature of Māori, politically, mentally and physically is documented.

Being cautious is part of Māori culture and atua or gods are some of its earliest artefacts. Tangaroa is one of the great Māori and wider Polynesian gods. He is the god of the sea, rivers, lakes and all life within them. He is venerated around Polynesia as Tangaroa-nui, Tangaroa-ra-vao, Tangaroa-mai-tu-rangi, Tangaroa-a-mua, Tangaroa-a-timu, and Tangaroa-a-roto, Taʾaroa, Tangaloa and Tangaroa, and Kanaloa. And while Christianity has displaced indigenous deities, Tangaroa survives due to the ongoing importance of the sea to Polynesian communities. As such, the practices of Tangaroa also survive, karakia or prayers to Tangaroa and his many guises are still practiced as are rāhui that prohibits seafood gathering in recognition of a sea fatality or to protect certain fishing grounds from being over used.

Tangaroa has a reputation of being omnipresent which promotes the need to be cautious. The whakatauki or proverb, Tangaroa Piiri Whare or Tangaroa is hiding in the house implies that Tangaroa is invisible and hears all; to be careful as the “walls have ears”. This is reiterated in another kiwaha; Ko Tangaroa ara rau (Tangaroa of many paths).

Skeptics may assign Tangaroa and other cultural artifacts that reinforce Māori being cautious to the history books, but here’s three reasons to reconsider:

- In 2013 a Statistics New Zealand national survey reported, 373,000 (70 percent) Māori adults said it was at least somewhat important for them to be involved in things to do with Māori culture. Māori culture including a want of it, therefore resonates with Māori.

- Story telling or narratives is recognized as a good way to promote health and safety. It seems practical to utilize stories such as Tangaroa Piiri Whare to unlock and motivate Māori or indeed other workers, to become more cautious.

- I recall Drew Rae saying something alike, don’t take the uncertainty away from health and safety, it makes people think they’re safe and similarly Todd Conklin commenting, you have learn to be unsafe in order to be safe. Safety can be measured, managed and therefore audited. It’s an ideal situation that assumes workers are safe as long as they play within the safety of the sand box. Caution on the other hand, is more of a daily journey towards achieving safety. It is caution that can help keep Māori workers safe not safety by itself – we’ve forgotten that and concealed it with safety clutter.

“Kia tūpato” use to be commonplace until it was displaced by “safety”. For Māori workers, caution is quite possible their most intuitive and least path of resistance to attaining a Safety-II outcome.

There’s definitely a place for safety as an outcome but given the current disparity in workplace harms, there’s a pressing case to reprise the use of “caution” as a path to achieving safety for Māori workers.

Instead of safety or safer I think that tūpato or caution is more apt and relevant for Māori workers. It maybe a simple case that Māori workers are better at behaving cautiously than at adhering to safety systems that curb caution. Leaders especially employers, could consider that dynamic and recognize more cautious behaviors into their systems and practices but I guess that’s something I will need to find out as part of my research.

As always I value in your feedback. In the next post I’ll discuss another element of the Mahi Haumaru (Work Safe) Model “Manaaki”.

Similarly, Mahi Haumaru functions on a basis of construction, if tupato, ako and manaaki are being used then Māori values or precepts can be evidenced as being used to improve health and safety. Their application is not a thing but an event because it is a result of conscious decision. The Model is not intended to recommend specific health and safety interventions or practices (e.g. how ako is practiced). It only provides the key underlying values or context for Māori practices in workplace health and safety to occur. While ako, tupato, and manaaki are not the only precepts and practices that can be used in health and safety, they are at the fore in terms of harmonizing a Maori worldview and western health and safety conventions.

Similarly, Mahi Haumaru functions on a basis of construction, if tupato, ako and manaaki are being used then Māori values or precepts can be evidenced as being used to improve health and safety. Their application is not a thing but an event because it is a result of conscious decision. The Model is not intended to recommend specific health and safety interventions or practices (e.g. how ako is practiced). It only provides the key underlying values or context for Māori practices in workplace health and safety to occur. While ako, tupato, and manaaki are not the only precepts and practices that can be used in health and safety, they are at the fore in terms of harmonizing a Maori worldview and western health and safety conventions.

I have been asked, “how do I incorporate indigenous knowledge into workplace health and safety?” I offer two steps:

I have been asked, “how do I incorporate indigenous knowledge into workplace health and safety?” I offer two steps: So what?

So what?